Research & Process

The Evolution of Cupid and Eros

A comprehensive analysis of the iconographic evolution of Eros/Cupid, contextualizing Arjan Spannenburg’s "CUPIDO" series within the Western art canon. The series bridges 17th-century chiaroscuro techniques and 19th-century Academic realism with contemporary digital photography. Key themes include the transition from "putto" to "adolescent Eros," the psychological depth of the Cupid and Psyche myth, and a stylistic dialogue with masters such as Rubens, Bronzino, and Caravaggio. Ideal for researchers, curators, and collectors interested in the intersection of classical mythology and modern fine art portraiture.

An Artistic Quest by Arjan Spannenburg

Desire, lust, and attraction, emotions we have attributed to Cupido, the God of Love, for centuries. For many, his name (or his Greek counterpart, Eros) evokes the image of a winged baby aimlessly firing arrows, an innocent symbol for Valentine’s cards.

However, art history tells a far more complex story. Eros was not always a putto (baby). In his origins, he was a man, an entity that brought both chaos and order, feared and adored. How did he transition from a powerful young man to a mischievous child? And what does this transition reveal about our evolving perception of love?

To understand this, we must return to the myth that sealed his fate: the love of Cupido and Psyche.

A Love in the Dark: The Myth of Eros and Psyche

The most defining narrative for Eros is his tragic and heroic love for Psyche. It begins with beauty so breathtaking that Psyche, a king’s daughter, was feared rather than courted. An oracle decreed she was destined for a monster. Yet, she was carried by the west wind to a palace of impossible beauty.

Eros visited her only under the cover of night, leaving before dawn. His reason was profound: he wished to be loved as an equal, not worshipped as a god.

The Temptation of Light

Driven by suspicion, Psyche eventually lit a lamp to see her lover's face. Instead of a monster, she found the most beautiful being imaginable. In her shock, a drop of hot oil fell from her lamp onto his shoulder. Eros awoke and fled, uttering the bitter truth: "Love cannot dwell where suspicion lives."

The Evolution of Form: From Youth to Putto

The way Eros is depicted often reveals the type of love an artist intends to convey: playful and fleeting, or overwhelming and sexual. In Greek antiquity, he was a "slender youth." It was only later, influenced by satirical texts, that he evolved into the chubby Renaissance Cupido.

Blindness and Eroticism in the Renaissance

Sometimes the form is used to deliver a moral message. In Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera, Cupido appears as a blindfolded child, symbolizing the randomness and "blindness" of infatuation.

In sharp contrast, Agnolo Bronzino presents a far more provocative interpretation. In his allegory, Cupido is an erotic teenager. Here, nudity is not about innocence; it is a direct reference to physicality, fertility, and seduction.

The Realism of Caravaggio: Love as Flesh and Blood

Caravaggio famously refused the safe, polished path. In Amor Vincet Omnia (Love Conquers All), he painted Eros as a real street boy with wings. He is defiant, laughing, and human, possessing a messy reality rather than marble perfection.

This earthy, whimsical depiction suggests that love is not a lofty, distant ideal, but something confrontational and close. This same raw energy is found in later neoclassical sculptures, which sought to balance divine grace with the athletic form of a maturing youth.

Even in the 19th century, artists like William Bouguereau continued to play with this adolescent form, capturing a sense of melancholy and transition that bridges the gap between the divine and the human.

A Modern Interpretation: The CUPIDO Series by Arjan Spannenburg

This art-historical journey brings us to the present. In my photography, I feel a strong kinship with Caravaggio and the classical Greek vision. Why reduce the God of Love to a decorative cherub when love itself is so complex, raw, and mature?

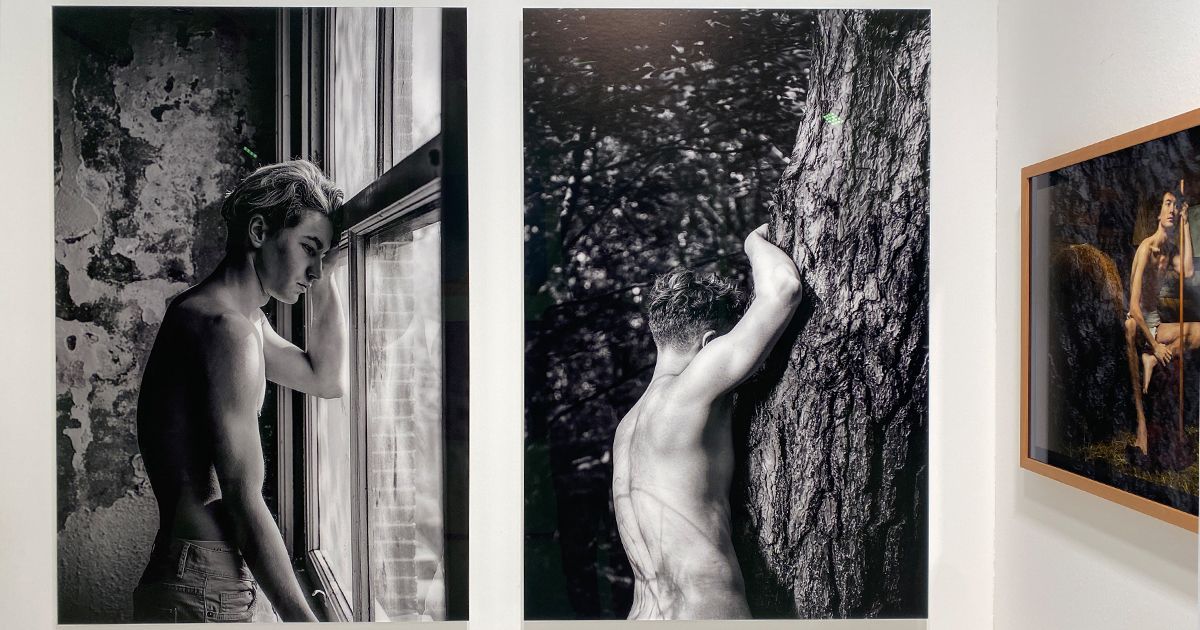

With my series CUPIDO, I break from the tradition of the putto and return to adolescence. This is the phase of transformation: the transition from child to man, mirroring the original Eros.

A Dialogue with the Masters

Where most of my work explores the abstraction of black-and-white, I consciously chose color for this series. It is an ode to classical painting. The warm skin tones and blonde hair of the model contrast with deep, petrol-green backgrounds, a nod to the nights where Eros and Psyche met.

In my series, the traditional symbols, the wings and arrows, are present, but the posture conveys the weight of responsibility and the dawn of self-awareness.

In works like Blind and The Quest, I investigate the shadow side of the myth. Here, Cupido is not just the hunter, but also the prey of his own emotions.

The Vulnerability of the God

The paradox of the CUPIDO series lies in portraying the God of Love as vulnerable and uncertain. Set against shadowy, forested environments, the figure navigates the darkness while bearing the tools of his power.

For me, love is not a baby. It is a transition, a powerful, human, and often heavy burden of the heart. Through this series, I invite collectors and curators to look beyond the Valentine’s cliché and see the Eros that has haunted art history for millennia: the beautiful, dangerous, and deeply human god of our desires.

Are you interested in adding a piece from the CUPIDO series to your collection?